We want to help you take meaningful steps to maintain the importance of sex in reproductive healthcare. Many people stay silent out of discomfort, embarrassment, dislike of making a “fuss” and sometimes fear. They find their voice when they know they’re not alone.

This toolkit is for you if you’re a midwife, maternity support worker, lactation consultant, a breastfeeding peer supporter, a maternity and neonatal voice partnership (MNVP) representative, a doula, an antenatal educator… if you are anyone involved in supporting or caring for women and their reproductive health, whether that’s fertility, pregnancy, birth and postnatal period, or other health concerns.

This toolkit comes from our observations of the way the importance of our sex is minimised, ignored or denied, and our experiences in confronting the results.

We are looking at situations that arise

- At work.

- In universities and colleges.

- In workplace training.

- Voluntary organisations.

- Healthcare settings.

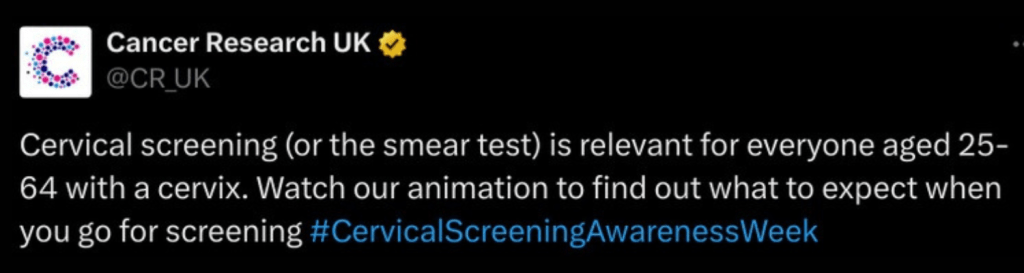

- Public health communications.

- Social media.

It is designed to

- Provide helpful resources and references.

- Suggest easy phrases or ideas you can use to challenge changes.

- Recommend strategies for resisting the erasure of sex.

- Inspire with positive stories.

- Give you a context and show you are not alone.

- Give you the background you need to ask the right questions and help protect yourself from any unfair retribution.

Note: this toolkit is not intended as legal advice. It has been compiled by women who live in the UK, and our experience, knowledge and focus is inevitably there. Different countries face different situations and of course different responses. However, some of what we say here will apply wherever you are.

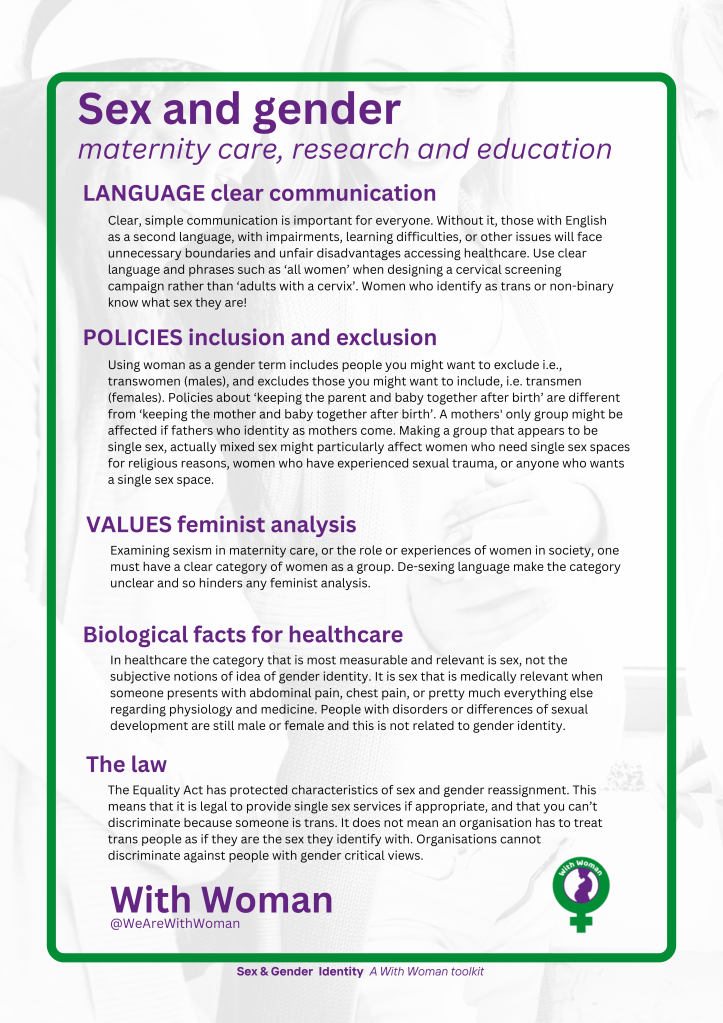

Sex is a primarily biological term which categorises females (women) and males (men).

Sex is important in health care and specifically important in reproductive health care.

Gender can mean

- A polite word for sex. Partly because that same word is used to mean sexual intercourse, it became normal to replace “sex” with “gender” for example on forms. You can see it used in this way in many policy documents where it is intended as a synonym for sex. It can also be intended as a synonym for ‘gender identity’ (see below).

- A power dynamic and set of sex stereotypes. By this we mean a socially constructed set of social norms which result in a mechanism of expectations and exploitation by men over women. Sex stereotypes are hierarchical with stereotypes and expectations placed on men frequently having higher social value and prestige than those ascribed to women. For example, the idea that women are less rational, that their caring natures mean they are more suited to doing the majority of unpaid domestic work. This is a basic feminist understanding of gender (gender stereotypes harm men too, but that is not our main concern here).

Gender identity is

- A personal, internal connection with notions of femininity or masculinity that is not necessarily linked to your sexed body. Not everyone believes they have a “gender identity“, but the rising popularity of the idea means that sometimes the terms “woman” or “man” now relate to how you feel inside, rather than your physical body.

This is the core of the new gender ideology. It implies that language and belief create reality. We don’t agree with this. When people claim a gender identity, their explanation often involves identifying with various sexist stereotypes.

Elevating gender identity and allowing it to become more important than sex, conflating it with sex or even erasing acknowledgement of sex altogether, is harmful and confusing, particularly in health literature which needs to be universally clear and accessible.

Over the past few years, institutions, organisations, businesses and services from small ones (like a locally-based new mums’ group) to large national and international ones (such as public broadcasters, or a country’s health service) have been adopting so-called “gender neutral” or “inclusive” language, and in some cases changing policy accordingly, by writing this language into legislation.

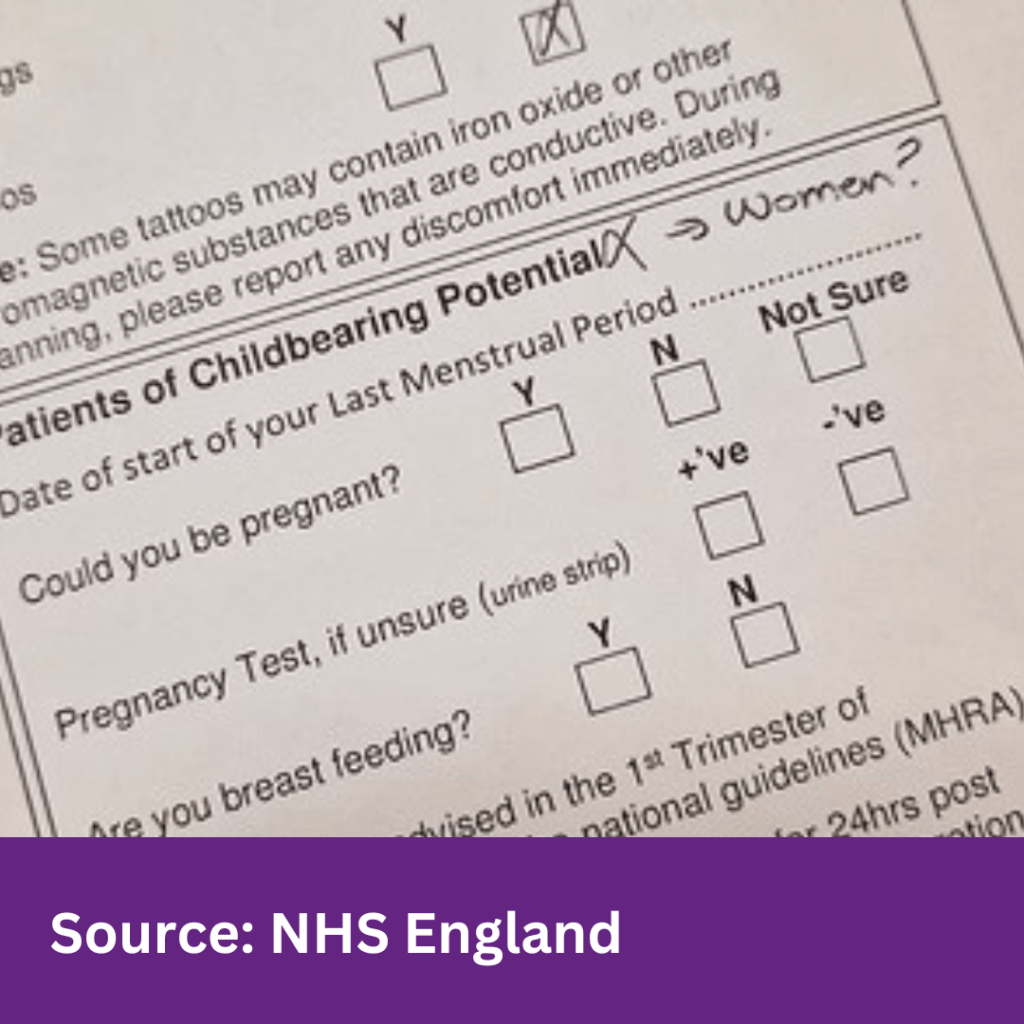

For example you may see “woman” or “mother” in pregnancy information has changed to “birthing person”. A request for a female caregiver may mean you see a male doctor or other medic or carer who identifies as a woman.

The fact that this language change does not generally happen in men’s health services itself reveals a sexist element.

Changing communications or policies to make “woman” seem something fluid you can cast off (or acquire) is harmful to women and girls. “Woman” and “mother” are already inclusive words: they embrace everyone who is female, everyone who is pregnant, whatever their sense or understanding of identity. Sex-based language describes the material, biological reality of female bodies. We consider that the following are some of the potential harms of using de-sexed language in reproductive and women’s healthcare:

- Using de-sexed language (sometimes known as “inclusive” or “gender neutral“) is confusing. Not everyone reads or speaks English fluently. Replacing common and established words (like woman, mother, breastfeeding) with de-sexed terms (like uterus owner, birthing parent, chest-feeding) makes health literature harder to navigate for some women accessing services. It’s not ‘inclusive language’ if the effect is to make the language more difficult to understand.

- De-sexing language to be more “inclusive” or “gender neutral”, sometimes misrepresents factual information. When talking about conditions that only affect females, it’s statistically wrong to say (for example) “1 in 10 people are diagnosed with endometriosis“.

- There can be a lack of clarity about what being a woman means. This is detrimental to women and girls (in fact, all young people). It changes the meaning of “woman” and other sex-related words (like mother, female, sister) into “gender identities”, which men can choose to share. “Woman” then includes those it should not (males who identify as being transwomen) and excludes those it should include (females who identify as transmen or non-binary). “Additive language” (“women and people with uteruses” and similar phrases) also produces this confusion. It makes the text more complex, and puts the sexed word literally alongside the de-sexed one.

- Obscuring the difference between male and female people and their health needs is unethical. Not being clear about the potential health implications now and in later life (for example, differences in male and female experiences of cancer, dementia, heart disease) inhibits people’s ability to manage their own health and well-being.

- It may compromise trust in healthcare professionals. If HCPs and others in a helping or support role use language that suggests they believe something that you know to be untrue (for example, that men can give birth, or breastfeed) it undermines trust in other advice too.

- It hides the sexism inherent in health care. Part of this comes from male bodies being the standard. Women often experience a lack of appropriate and timely healthcare because of the research and a data gap in women’s health. Women’s health needs are not the same as men’s, this is often overlooked or ignored in research.

- Removing sex from language can be culturally insensitive, and for some groups removing respect for the position of “woman” or “mother” may be confusing or offensive.

Chapter Two: Steps you can take >>